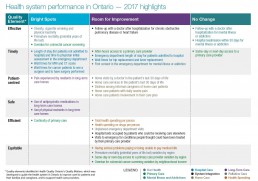

Excellent Care for Many, But Not All.

Entering its second decade, Measuring Up 2017 marks the 11th year of Health Quality Ontario reporting to Ontarians on the performance of their health care system. This year’s report focuses on a set of highlights of importance to Ontarians, drawn from a review of a set of about 50 health system indicators called the Common Quality Agenda. Measuring Up 2017 combines a broad range of data with the stories of people at the front lines of the system, including patients, families and health care professionals. From this combination of data and personal narratives, we learn what’s working well and what needs improvement in our health care system.

Where we’re doing well

Premature mortality

The big picture of health in Ontario looks good: people are living longer, and losing fewer years of their lives to premature death. Ontario has the lowest premature mortality rate in Canada, and it improved to 4,221 potential years of life lost per 100,000 population in 2013 from 5,120 per 100,000 people in 2003.

Continuity of care

A majority of Ontarians who saw a primary care doctor three or more times over the previous two years had at least three-quarters of their visits with the same doctor. High continuity – being able to see a regular primary care provider at least three quarters of the time – improves patients’ health outcomes and reduces unnecessary emergency department or hospital use.

Prevention and screening

Improvements in illness prevention and screening have kept more people in Ontario healthier. The rate of people being overdue for colorectal cancer screening has improved to 38.7% in 2015 from 43.6% in 2011.

Wait times to see a surgeon

Measuring Up 2017 marks the first time we are able to include wait times to see a surgeon. The proportion of cancer patients seen by a surgeon within the target wait time ranges from 83% to 87% depending on the priority level.

Cancer surgeries within target time

There has been some improvement in the wait time from the decision to have cancer surgery to the time of surgery, with the proportion of cancer surgeries that met the target increasing year-over-year between 2008/09 and 2015/16 for all priority levels.

Long-term care

Among long-term care home residents, the percentage who experience pain has improved overtime, to 6.1% in 2015/16 from 11.9% in 2010/11, the use of daily physical restraints has been reduced to 6% in 2015/16 from 16.1% in 2010/11, and the use of antipsychotic medications among residents without dementia has been reduced to 22.9% in 2015/16 from 35.0% in 2010/11.

How is your region doing?

How does your Local Health Integration Network (LHIN) region compare to the provincial average:

Note: Cycle pages above (>) to see additional indicators (Life expectancy, potential years of life lost)

Where we need to improve

Access

Timely access to care is an ongoing issue for patients in Ontario’s health system. Fewer patients have surgery within the target time for hip and knee replacements – both increasingly common procedures. For example, 80% of patients who had Priority 4 knee replacement surgery (the category of knee replacement with the greatest number of surgeries) had them completed within the target time in 2016/17, compared to 85% in 2014/15. Little progress has been made in reducing the proportion of people – 33.1% in 2015 – going to the emergency department for a mental illness or addiction, who had not seen a doctor or psychiatrist previously.

Caregiver distress

Distress is on the rise among informal caregivers (usually family or friends). Continued distress among informal caregivers of patients who needed home care for at least a few months increased to 24.3% from 21.2% between the first half of 2012/13 and the first half of 2016/17.

Transitions

The system fails many patients as they transition from one care setting to another. The time patients spend in the emergency department before being admitted to hospital is not improving (15.2 hours, on average, in 2016/17), while many patients are in hospital beds who could be receiving care elsewhere, such as a long-term care home or home care (13.9% of inpatient days in 2015/16). When patients are able to transition to receiving care at home, only 56.7% strongly agree that they felt involved in the development of their own care plan.

Palliative care

For those patients who are at the end of life, too few are able to receive timely palliative care in their home, even though this is what patients want (only 27.5% of people received a palliative specific home care visit in 2015/16, in their last 30 days of life). More than half (54.8%) of people who died in 2015/16 had an unplanned visit to the emergency department in their last 30 days of life, which could indicate that they did not receive the care they needed in the community.

Equity

Some people in Ontario are much less likely than others to receive quality care. Ontario’s overall premature mortality rate has improved, but there is striking variation by region. The rate of potential years of life lost was nearly 2.5 times higher in the North West LHIN region, at 7,647 years per 100,000 people, than in the Central LHIN region, at 3,026 years per 100,000 population, during the period between 2010 and 2012. Same-day or next-day access to primary care providers remains a challenge, particularly in rural and remote areas, ranging from a low of 22% in the North East LHIN region to a high of 60.3% in the Central West LHIN region. There are inequities by income for colorectal cancer screening. Among urban residents, those in the lowest-income neighbourhoods had the highest rate of being overdue for colorectal cancer screening in 2015, at 46.5%, compared to 32.7% of those in the highest-income neighbourhoods.

How is your region doing?

How does your Local Health Integration Network (LHIN) region compare to the provincial average:

Note: Cycle pages above (>) to see additional indicator (Average time admitted patients spent in ED)

Beyond our provincial borders: How Ontario compares

Average to good

Compared to other provinces and countries (where data are available), the results of Ontario’s health system are mixed. Ontario had the lowest rate of potential years of life lost due to premature death in Canada. Ontario is also doing comparatively well in terms of quality of care in long-term care homes – best or second-best among the five provinces with comparable data when it comes to a reduction in residents experiencing pain, antipsychotic medication use and restraint use. Ontario is in the middle of the pack in terms of access to primary care outside of normal hours.

At or near the bottom

Compared to 10 socioeconomically similar countries, Ontario is the worst in terms of patient reported ability to get a primary care appointment the same or next day when sick. And compared to nine socioeconomically similar countries, Ontario is a costly system for drug spending –fourth in the amount per person spent on drugs. About 1 in 12 people in Ontario reported having serious problems paying their medical bills.

How is Health Quality Ontario helping to improve care?

Measuring Up 2017 reflects Health Quality Ontario’s role in reporting on the quality of the health care system. But our mandate is much broader, including a commitment to support active improvement in care. Here are some of the ways that Health Quality Ontario works with other sat each level of the health care system to ensure better care for all:

Health Quality Ontario developed a provincial framework, Quality Matters, as a common guide for the health system to improve care for patients and their families and caregivers, and to support health care providers. Quality Matters defines the culture of a high-quality health system according to six dimensions: safe, effective, patient-centred, efficient, timely, and equitable.

More than 1,000 organizations in Ontario involved in hospital care, home care, primary care and long-term care have created annual Quality Improvement Plans – documented sets of commitments to improve the quality of the care they provide, through focused targets and actions. Regional Quality Tables across Ontario, each chaired by a Clinical Quality Lead, share local experiences and initiatives aimed at improving quality of care, and work to align and connect regional and provincial quality programs.

ARTIC (Adopting Research to Improve Care) initiatives are supporting the implementation of proven service delivery models. These include central intake and assessment centres for patients with common musculoskeletal conditions, including back, neck and shoulder pain, and those who may need hip and knee replacements; and Patient Oriented Discharge Summary (PODS), a tool to ensure patients have the information they need before going home from the hospital.

Health care and services in Ontario often involve sophisticated technologies. Health Quality Ontario performs regular Health Technology Assessments of new and existing health care services and medical devices. A group of experts, leaders and patients that form the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee makes scientific evidence-based recommendations to the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care on whether these health technologies should be publicly funded.

The Ontario Surgical Quality Improvement Network, supported by Health Quality Ontario, provides resources to surgical teams across the province to improve quality in surgery, as well as improved patient experience and outcomes. Health Quality Ontario is also working with patients, caregivers and doctors to develop quality standards that identify the care patients should be offered for specific health conditions such as depression or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, based on the best available evidence.

Elgin

Trust and empathy

Elgin’s parents knew their son was in a bad state. He had just graduated from law enforcement training and was looking to get a job with the police force. But long hours working in a hospital kitchen, plus a second job doing business promotions in Toronto’s entertainment district left Elgin stressed out, exhausted, and barely getting any sleep. He was suffering from insomnia and started having delusions during the day. “I was talking nonsense, saying all kinds of strange things,” Elgin recalls.

His parents rushed him to the emergency department at the hospital in Scarborough where he worked. When the doctors came to see Elgin, he took off running, convinced they were out to get him. He eventually returned to see the doctors.

He was admitted to the hospital’s psychiatry department, put in physical restraints, and injected with medication. Doctors diagnosed him with schizophrenia, although he says they didn’t do a thorough assessment. Elgin stayed in hospital for six months, watching out the window as the seasons changed. This emergency department visit and hospitalization was Elgin’s first experience receiving mental health care.

When he left the hospital, Elgin returned to work and was doing a little better, but he found the medication he had been prescribed made him very tired. “I didn’t like how it made me feel, so I stopped taking it. I had various relapses. It became like a revolving door with me in and out of hospital.”

He also experienced stigma around his illness, which affected his relationship with his partner at the time. When they broke up, Elgin became homeless. He stayed at a shelter for a few days and then went back to the hospital for help. “You’re not a danger to yourself or anyone else, they told me – we can’t admit you,” Elgin says.

Two days later, Elgin, experiencing delusions and hearing voices in his head, decided he had to leave the country. He took a taxi from downtown Toronto to Pearson Airport, convinced that he had to fly to Chicago because Michael Jordan wanted him to try out for the Chicago Bulls basketball team. Elgin bolted through the security checkpoint,punching and shoving people who were trying to stop him. He ran down the gangway entrance onto the airplane and into the cockpit with the pilot and co-pilot. After a few minutes, Elgin opened the cockpit door and was immediately pepper-sprayed and tackled to the floor.

After the plane incident, Elgin was taken to two different correctional facilities and says he didn’t receive any treatment for his mental illness for three months. “I spent a lot of time banging on the door (of his cell) and yelling, and going back and forth to court,” he says. Eventually, he saw a psychiatrist who reassessed his condition and told him he had bipolar mood disorder, not schizophrenia. He started a new medication and responded well to it. For his court case, he received an absolute discharge on charges of hijacking and assault. “I didn’t realize the charges until I was stable,” Elgin says. “I started feeling really depressed about what had happened and the people that I had hurt.”

Elgin is now married, and he and his wife have a 14-year-old daughter. He tried applying to become a police officer but wasn’t successful. At another job he applied to he noticed a sticky note on his application that said: “We can’t hire this person because he’s schizophrenic and has mental illness.” He persisted and became a licenced financial advisor who helps people who have a hard time qualifying for life insurance.

Every four months, Elgin, now 46, visits his long-time psychiatrist. “I’m very fortunate to have a good psychiatrist,” he says. “We have a trusting relationship. Now I’m stable.” Reflecting on the past 25 years of mental health care, Elgin wishes there was more care, and that people with mental illness had more resources available to them. “People need to really listen to the patient and how they’re feeling,” he says, “and then follow up with them afterwards.”

Other stories

“I owe Homeward Bound my life. I was about ready to give up when I met them,” says Andy, 42, a transgender Indigenous man who struggles with mental illness and now – after living on the street, in shelters and on friends’ couches – has his first real home in 10 years thanks to De dwa da dehs nye>s Aboriginal Health Centre’s Homeward Bound program, that focuses on Indigenous people.

Andy’s friend, herself a Homeward Bound client, convinced him to try the program, despite his bad experiences with other places. “Some shelters have kicked me out. One men’s housing program put me on a wait list, but they would only use my birth name, Amanda… To me that’s lying about who I am. I can’t do that anymore.”

Homeward Bound was different right from the first visit, says Andy. “Tyson [his case manager] brought me paperwork that all said ‘Andy.’ He told me about a native tradition that says trans people are ‘born with two spirits and have extra wisdom to give’… No one calls me an ‘it’ here. No one says ‘born a girl, stay a girl’ like at other places.”

Within a month, Tyson had helped Andy find a bachelor apartment; Homeward Bound provided some funds to buy furniture. Andy’s income is through the Ontario Works program, and he gets $250 monthly rent subsidy from the City of Hamilton for five years.

Andy works hard to overcome crippling agoraphobia (fear of leaving home and of strangers) to ride his bicycle around town to see his nurse-practitioner, Michelle (part of Homeward Bound), meet with his therapist, and participate in art classes, hiking trips and Indigenous cultural events.

Andy was surprised to learn he was adopted – and of Indigenous heritage – when a family member blurted it out last year. “My native culture is becoming more important to me… I’m on my healing journey,” says Andy. “Before, it was just meds and psychiatrists… not the greatest, I never got better.” He’s been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as well as agoraphobia.

Homeward Bound has connected Andy with mental health services at the De dwa da dehs nye>s Aboriginal Health Centre in Hamilton, and introduced him to Selby Harris, a counsellor with the Hamilton Regional Indian Centre who sees Andy weekly, sometimes out in nature, or at Andy’s home on the days Andy can’t face the world. Homeward Bound also helped Andy find a new family doctor who specializes in providing care to individuals who are transgender. “It’s amazing,” says Andy. “The doctor is really respectful, everything is under ‘Andy’ even though my health card still has to say ‘Amanda.’” (He’s learned that can change if he gets the sex designation on his birth certificate changed, which he’s begun working on.)

Tyson visits Andy at home every week. “He always asks me what I need. One time I said, ‘I need to paint.’ He went out and came back with a bag of canvases, paints and brushes.” Andy’s eyes light up. “I’ve made art since I was little. I paint my feelings.” His apartment walls are covered with his abstract artwork.

Andy is proud to be 16 years sober from drugs, and three months clean from cutting and other forms of self-harm. “I’m getting out, I’m talking more. I’m smudging [cleansing by burning traditional medicines]. I’m learning as I go.” He shows off his new left wrist tattoo: a small dark tree with roots, directly below the bold capped words BELIEVE IN YOURSELF. He plans to have more roots inked, going up his arm.

“I’m growing roots, I have a home. I have a community now.”

Lilac, 51, says she’s survived, and thrived, in her long experience with kidney disease in large part because of continuous care by the same family doctor. “I trust her with my life,” she says of her family doctor, and she’s had to do just that.

After six years with no family doctor (she grew up with her family doctor, who retired), Lilac noticed “my ankles started swelling, and elevated hypertension caused me to feel my blood coursing through me,” so she took a doctor referral from a friend. At her first and only visit to that primary care provider, Lilac says she was told to wait for the doctor with no appropriate coverage and when the doctor came in, she didn’t do anything to address it, recalls Lilac, still embarrassed about the incident. She didn’t return to this primary care provider and continued her search for a new family doctor. “I need to feel they care, and not treat me like a number.”

Through a referral from a trusted co-worker, she found her current family doctor with whom she felt comfortable and who, after tests, immediately referred Lilac to a kidney specialist. “Heavy fluid retention bloated me to the point of imprinting the chair on my skin,” she recalls. The specialist ordered a biopsy and put her on medications, checking on her progress a few days later.

Diagnosed at age 36 with first one, then two, kidney diseases, Lilac says she was fearful of what the future held. As a young adult, she’d lost her father to cardiac arrest during his dialysis when he was 57. She had been very close to him, and Lilac says memories of his hospitalizations resurfaced when she started dialysis.

Once diagnosed, she struggled to process her diagnosis. “It was my choice to keep this to myself. I associated it with a personal failure … [and] my mom requested for me not to share my disease with members of her circle. It’s a cultural thing,” says Lilac, who is first-generation Chinese-Canadian. “There is a stigma about losing face, not for the family, but for others not to judge me.”

That changed in 2012 at age 46 when Lilac began dialysis, a process where she had to spend up to 18 hours a week in the hospital with machines carrying waste and water out of her blood. She met a fellow dialysis patient who was also keeping his disease secret from the world. “His self-imposed isolation made him a very lonely man,” recalls Lilac, who decided to begin blogging updates, about how her disease doesn’t have to stop her from living, to good friends in her life.

Lilac had pneumothorax (collapsed lung) due to complications from peritoneal dialysis. In 2013, while she continued on dialysis, the hospital spent a year running transplant workup tests to ensure her body would survive the surgery. In 2014, once officially approved to be on the transplant list, Lilac was extremely grateful to receive a kidney within months (she was told it would be a four-to-six year wait). She’s glad her mom, 83, lived to see Lilac transplanted and healthy; she died eight weeks later. Lilac now gives back by helping others: she is a volunteer in the Patient Partnerships program to help general hospital planning and decision-making at the Toronto hospital where she was treated; an external stakeholder on the University of Toronto Bloomberg Institute’s Faculty Council; and a peer support volunteer with the Kidney Foundation of Ontario.

Through it all, Lilac’s family doctor has been a pillar of support. “I feel grateful I’ve had my current family doctor throughout my journey; we have history together,” Lilac says. “She is a mentally strong woman who used to run marathons. She leads by example and has remained caring, trustworthy, knowledgeable and transparently honest throughout my health journey. Although I see her every two years for general physical or for other non-transplant medical concerns, my transplant team sends her regular updates on my overall health.”

Lilac emphasizes that her doctor is much more than just a clinician. Upon one visit to ensure all vaccinations were compatible for a transplant patient, “she realized that I was about to celebrate a milestone birthday. She turned off her laptop, faced me and said, ‘You’ve looked your mortality not once, but twice, in its face and survived to tell the story. Not very many people have had that happen before the age of 50. This calls for a celebration.’ When I replied ‘How would you celebrate?’ my doctor said, ‘this is about you, this is your journey. It all depends on where your head space is and where your heart is.’ Her medical skills plus spiritual side makes her unique as a primary care provider.”

One of the main reasons Shawn Dookie became a nurse practitioner was to be able to provide his patients with ongoing, continuous care that would help them when they were sick, but also benefit their overall health in the longer term. “I like building a relationship with people,” says Dookie. “I like not having to rush through a conversation with a patient. I can take my time and provide health teaching and really explain things to people so they can own their own health.”

That approach to caring for patients proved invaluable when Dookie started to work as a nurse practitioner in Thunder Bay. He had previously been a registered nurse, but returned to university to complete the nurse practitioner program that would allow him to take on additional responsibilities such as diagnosing and treating common illnesses, performing physical check-ups and prescribing certain medications.

At the nurse practitioner-led clinic where he first worked a nurse practitioner, Dookie found he needed ongoing connections with his patients just to learn enough about their lives to be able to care for them in the way he wanted. Many came from Indigenous, francophone, or socioeconomically disadvantaged communities that he had little experience with when he was a registered nurse working in Toronto hospitals.

“The culture is much different up here, where you (patients) don’t believe what the health care providers tell you until you’ve had the chance to really build up some trust with them,” says Dookie.

Cultural differences meant not only that Dookie had to take the time to get to know his patients, but also that he sometimes had to treat their health issues differently than he might have for patients in the south. For example, he learned that with some patients he had to take a slower, more conservative approach at first to treat chronic conditions such as diabetes, until he gained their confidence.

“You really have to take that time to build a relationship with people,” he says. Dookie also found himself serving a group of patients with complex needs, who had chronic conditions that required continuous care. Many had had difficulty obtaining primary care elsewhere.

“So you get someone who’s applied to three different clinics and been declined because of their past medical history,” explains Dookie. “If you’re a healthy young person it’s easy to get care – but if you’re a 40-something-year-old person with schizophrenia, diabetes and a head injury, nobody’s going to want to take you on as a patient, so that tended to be a lot of the patients we were taking on at the nurse practitioner-led clinic.”

Dookie believes nurse practioners, while they can’t replace doctors, can play a positive role in improving access to health care in the province.

“I think that we can manage a lot of things like chronic disease, like preventative care, like public health. We can manage a lot of that stuff very safely and effectively, if we are given the right resources.”

Dookie has recently moved on to work at another health centre in Thunder Bay, but takes the same approach to building trust, understanding and relationships with patients that he established at his previous job, so that he can provide them with the best care possible.

Thinking about what would make for a perfect day as a nurse practitioner, Dookie says: “I’d feel like I made an impact on their lives, I’d feel like their chronic disease is getting better, I’d feel like their knowledge of their illness is getting better, and I can directly attribute that to the impact that I am having on their care and the time that I’ve taken to take care of them. So that’s an awesome day.”

Everything was a blur. Gordon was sitting in a nondescript consultation room in a London hospital. The general surgeon had just told the University of Toronto law and MBA graduate student that tests had come back positive for testicular cancer. From there, Gordon didn’t remember much beyond walking in a daze down the hall to the urologist’s office. Two weeks later, he had surgery.

“When you get your diagnosis, you’re not thinking right,” Gordon says. “I remember very little of all that was said. I don’t remember much of anything.”

Gordon had originally seen his family doctor about pain in his abdomen and was referred to a general surgeon with a suspected hernia, He waited about four weeks to see the surgeon, who, after some tests that same day, determined it was cancer. The first cancer surgery was urgent, Gordon says, so he didn’t even think about having to wait. That all changed when the surgeon recommended a second, more complicated surgery that involved removing abdominal lymph nodes.

First, Gordon had to wait for pathology results, which took five weeks, followed by another four-week wait for his first meeting with the surgeon who would remove the lymph nodes. After he met with the surgeon, Gordon’s second surgery was scheduled for four weeks later, which brought his total wait time to about 13 weeks from the time he first found out he would need the second surgery.

“The waiting is frustrating because you know what needs to happen, but it’s hard not knowing when it’s going to happen, when you’re going to get a call,” Gordon says. “It’s hard to live a life between when you find out what needs to happen and when it actually happens. It’s a psychological barrier that I didn’t have enough help with, or know to reach out for help to manage the anxiety from waiting.”

During the wait for the second surgery, Gordon started skipping some of his university classes, and began to retreat from his normal life. He eventually stopped going to class altogether and didn’t see any friends. “The last week before my surgery I don’t think I left the house,” Gordon says. “I didn’t have the mental energy to go on acting as if things were normal.”

As hard as it was to wait for the surgery, Gordon is realistic about wait times. “When you’re a patient, any wait time seems like it’s too long,” he says. “But I also understand that it’s not as easy as adding more surgeons and more operating rooms to shorten the wait times. I wouldn’t want the wait times to come at the expense of anything else.”

The surgery was successful, and Gordon began chemotherapy a few months later. Over the summer, he was able to make up for the classes he had missed. Looking back on his care, Gordon says the providers were all individually very good, but communication could have been better with him and between themselves. Gordon spent a lot of time wondering when the surgeon’s office would call, not knowing what was going on. Doctors and nurses sometimes relied on him to convey his medical history and didn’t appear to have his complete files. When Gordon received home care after his second surgery, the nurses had “virtually no information” about him when they arrived the first time. “It was frustrating and very tiring to keep summarizing my story, especially as my medical history got longer and longer,” Gordon says. “It’s tiring at any time, and when you’re already mentally and emotionally drained, it was the last thing I needed.”

Gordon is slated to complete his JD/MBA (law and business) degree in 2019.

In September 2014 at age 22, Kyra went to the emergency department with what was first thought to be a bowel obstruction. That afternoon, she received the terrible news that she had ovarian cancer, and had surgery within a week to remove several tumours and all her reproductive organs. Months of chemotherapy followed, then the cancer returned, and there was more treatment and more chemotherapy.

Kyra was accompanied from nearly the beginning of her cancer treatment by a home care nurse, Karen Bowers, who visited her Windsor home to change her bandages and monitor her condition. Bowers’ visits made a “huge difference,” according to Kyra, particularly in helping her stay out of hospital, and in attending to her needs in a much more personal way.

“It’s more of a one-on-one thing with the home care.”

Kyra’s mother, Brenda, describes how Bowers has always kept Kyra and her family involved in the decisions about her care. “All I have to do is pick up the phone and call and she’s there answering questions,” says Brenda. “And when we have a rough patch, she takes the extra time with us, explains what’s happening.” While Bowers was a nurse regularly making home visits when she first started caring for Kyra, she’s now manager of clinical practice at the health care organization in Windsor that has been providing Kyra’s home care services. But she still visits Kyra regularly, acting as a support to her, her family, and the current primary care nurse who visits three times a week.

“I continue to see Kyra because I told her in the beginning that I would be a part of her care team until she beat cancer or until it beat her,” explains Bowers. “Obviously, we were both hoping for the former.”

For her part, Kyra has never wanted to throw herself a “pity party,” as she told the Windsor Star newspaper in 2015, when it published an article about her efforts to spread awareness of ovarian cancer. Rather, she said, “I’m just going to live each day as if I’m on this side of the dirt and that’s great.”

And so she has. But the cancer was not cured, and in March of 2017, Kyra decided it was time to stop seeking a cure and change her care plan to focus on palliative care, to keep her as comfortable as possible and allow her to remain at home instead of in hospital.

Two-and-a-half years after being diagnosed with ovarian cancer and undergoing several rounds of chemotherapy that failed to stop its progression, 25-year-old Kyra chose to receive palliative care. It has helped to make her more comfortable and allowed her to live at home in Windsor with her family, but she needs a lot of support.

“Kyra is basically bedridden now,” says her mother, Brenda. “She can make small steps with full assistance. I sponge bathe her every day, as our home is an older one that is not accessible.” Kyra sleeps 20 to 22 hours a day. In addition to being very ill from cancer, she has lost her hearing on the right side and has suffered nerve damage to her hands and feet as a result of chemotherapy, explains Brenda.

Kyra’s long-time home care nurse, Karen Bowers, still visits regularly to support Kyra and her family even though she has moved into a new job supervising other home care nurses. Bowers, who has specialty training in palliative care, visits about every two weeks to answer questions and help keep things running smoothly. Kyra’s current primary home care nurse visits three times a week for symptom management and to manage the intravenous line through which she receives all her medications.

As well, at the request of her family, Kyra’s care team has grown to include staff from a local hospice. A doctor and a nurse educator from there visit regularly, and a nurse practitioner has also visited. The hospice can be contacted 24 hours a day for additional help, and has also offered the family counselling and pastoral care.

Still, in order to make Kyra’s time with her family as calm and uninterrupted as possible, her mother has tried to minimize the number of care providers coming into their home.

“Brenda has been handling the majority of Kyra’s actual care needs, and uses the nurses for back-up and as a second set of eyes,” explains Bowers. “They are truly an amazing family.”

Brenda, however, credits the home care and hospice support Kyra has received with allowing the family to cope and to “come to terms with the outcome of this journey.” She notes all the options for her daughter’s care and the help available have been explained in detail to the family, and both home care and hospice staff have made sure Kyra’s wishes are a priority and that her care plan going forward is based on those wishes. “We are very lucky to have the team we have,” says Brenda. “The open communication has been key to Kyra’s care and now her palliative care plan. This journey has not been without bumps, but communication has helped clear up things and we have learned to listen first and take time before making decisions. This has made it easier for Kyra to have a greater understanding of her options, and for us as a family to have more understanding.”

In memoriam: Kyra died peacefully at home in Windsor on August 30, 2017.